- Climate

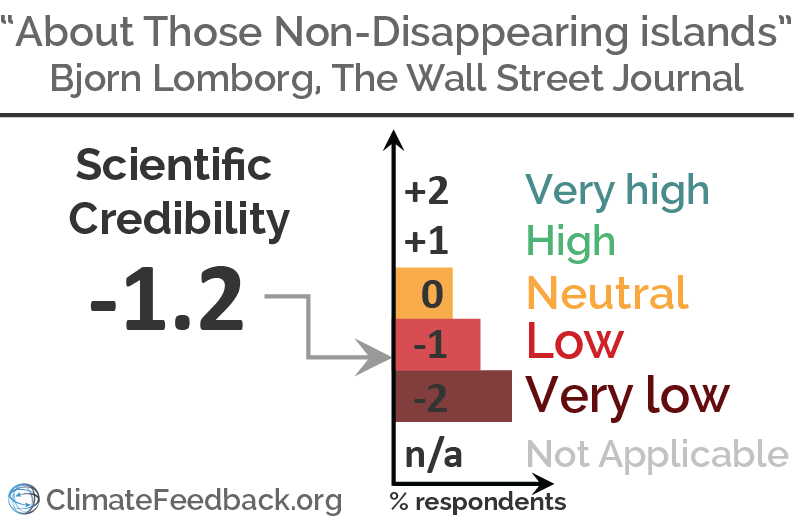

Analysis of "About Those Non-Disappearing Pacific Islands"

Reviewed content

Headline: "About Those Non-Disappearing Pacific Islands"

Published in The Wall Street Journal, by Bjorn Lomborg, on 2016-10-13.

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

This Wall Street Journal article comments on the fact that atoll islands in the Pacific are not all simply shrinking as sea level rises, because dynamic coastal processes can move sediment to build shorelines outward. However, the article doesn’t mention that sea level rise related to unchecked global warming would ultimately make many low-lying islands in the Pacific uninhabitable.

The author, Bjorn Lomborg, cherry-picks this specific piece of research and uses it in support of a broad argument against the value of climate policy. He also misrepresents the Paris Agreement to downplay its potential to curb future climate change.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

GUEST COMMENTS

Professor, University of New South Wales

This article is misleading. The dynamics of shorelines of low-lying Pacific Islands are complicated and influenced by many local factors. Climate change and associated sea-level change are the underlying trend that will “win” over long time scales. There are many wiggles and local anomalies that, if taken out of context and analysed over short timescales, might hide the overall trend. This article is a textbook example of cherry-picking–jumping to false conclusions based on a small sample of data that does not reflect the bigger picture.

Professor, The University of Auckland

There are a lot of claims that islands are passive geological entities that will sit there and drown. Our work shows that they are anything but static. They are dynamic. They move around and they can grow. So just because sea level is rising, it doesn’t mean doom and gloom for all atolls. Although the islands may survive into the future, the changes could still affect issues like fresh water and agriculture, potentially making life on these islands much more difficult than it is today.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Professor, University of Bristol

This article is very interesting because it exemplifies a highly-misleading rhetorical practice that is effective, frequently used, but not easily recognized by the public–and hence all the more damaging. This is known as “paltering” and the term was popularized by Frederick Schauer and Richard Zeckhauser in 2009 and refers to “fudging, twisting, shading, bending, stretching, slanting, exaggerating, distorting, whitewashing, and selective reporting.” A successful palterer will try to avoid being untruthful in each of his/her utterances, but will nonetheless put together a highly misleading picture based on selective reporting, half-truths, and errors of omission. As the commenters have pointed out, this is the case here. Unfortunately, paltering is difficult for non-experts to detect and the best defense against it is to know who engages in it and for what political purpose.

Assistant Professor, University of Virginia

Land area gains due to sediment accretion in the Marshall Islands and other low-lying coastlines do not necessarily indicate that coastal populations are spared from the effects of sea-level rise. I find the presented argument that the focus should be on reducing poverty and political corruption in the Marshall Islands rather than on cutting global carbon emissions not well supported and misleading to a general audience.

Research Associate, Harvard University

The article contains a number of logical fallacies – red herring, false dichotomy – that seem to be recurrent in Lomborg’s articles. He does point out an interesting and perhaps little-known fact about current land dynamics of Pacific atoll islands; however, this fact, in and of itself, does not all of a sudden make current concern about global climate change overblown and irrelevant, as the article somehow implies. His presentation of the Paris Agreement and discussion of the best strategy to address global warming is, in my view, dishonest and misleading.

Professor, University of California, Berkeley

In my view the author attempts to develop a polemic that funds spent on climate change are not benefiting the poor, and that there is, in fact, a choice between one and the other. This is demonstrably false, and yet the author repeats it despite the evidence.

Professor, Victoria University of Wellington

The effects of sea level rise on tropical Pacific islands are indeed complicated. Implying that climate change and sea level rise are therefore not urgent concerns is very misleading.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

Key Take-aways

The statements quoted below are from Bjorn Lomborg; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“Research shows that this process is overpowering the erosion from sea-level rise, leading to net land-area gain. This is not only true for the Marshall Islands. […]several studies have documented noteworthy shoreline progradation [growth] and positional changes of islands since the mid-20th century, resulting in a net increase in island area.”

Professor, Victoria University of Wellington

The dynamics of sand accretion and loss across the tropical Pacific is indeed complicated, and many atolls are at the moment growing. However, as sea levels rise in this area of the globe, water tables also rise and become salinated, reducing the availability of fresh water for drinking or agriculture. Focusing on the tropical Pacific takes attention away from regions where the signal is much clearer, e.g. the east coast of the USA. The occurrence of “nuisance flooding” and coastal inundation has risen dramatically in recent decades. Another 50-100 centimeters of sea level rise globally threatens vast swaths of built infrastructure and hundreds of millions of lives. Whether or not Pacific atolls accrete or shrink is not the most central issue.

Professor, University of New South Wales

This statement is oversimplified and cannot be generalised. For example, there is evidence from the Solomon Islands that five islands have disappeared in recent years while six others have experienced severe shoreline recession*. This evidence is based on time series of aerial and satellite imagery from 1947 to 2014 of 33 islands, along with historical insight from local knowledge: “Shoreline recession at two sites has destroyed villages that have existed since at least 1935, leading to community relocations…”

- Albert S et al (2016) Interactions between sea-level rise and wave exposure on reef island dynamics in the Solomon Islands Environmental Research Letters

Assistant Professor, University of Virginia

As wave energy and rising sea levels batter coastlines, the erosional products (i.e. sediments) can either be accreted onto the existing land or removed offshore into the deep ocean. Where the sediment is redistributed depends on a number of factors. Although sediment accretion can increase land area, it does little to change the elevation of low-lying islands, like the Marshall Islands. Therefore, people living in low-lying areas, even if there is historical land area gain, are still susceptible to inundation and damages due to storm waves, higher-than-usual tides (e.g. king tides), and sea level rise. These unconsolidated, loose sediments are also easily mobilized; therefore, localized land area gains by sediment accretion can be very dynamic on short timescales. This article could leave readers thinking that land area gains alone can mitigate the effects of sea level rise on low-lying coastal areas, but land elevation is what is really important.

“The most famous of these studies, published in 2010 by Paul Kench and Arthur Webb of the South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission in Fiji, showed that of 27 Pacific islands, 14% lost area. Yet 43% gained area, with the rest remaining stable.”

Professor, The University of Auckland

This comment does provide a reasonable assessment of the message of our article: that the majority of islands have become larger or remained stable and that islands are locationally dynamic on their reef platforms. We think these dynamic features do pose management challenges for island communities. However, all reports fail to reflect the nuances of our work.

Coastal geomorphologist, The University of Wollongong

What is for sure is that the island’s natural sedimentary systems will not just sit and be unresponsive. The islands will respond but we must be very careful to point out that ”response” does not necessarily mean that the islands will be maintained in the form we recognize today, that is, we do not know how long an island with soils for agriculture, complex vegetation, good fresh groundwater reserves, etc. can be maintained. Indeed, given what we understand of increasing rates of sea level rise we may be talking about relatively inhospitable gravel banks as the response to the next 100 years of sea level rise.

“It seems self-evident that rising sea levels will reduce land area. However, there is a process of accretion, where coral broken up by the waves washes up on these low-lying islands as sand, counteracting the reduction in land mass. Research shows that this process is overpowering the erosion from sea-level rise, leading to net land-area gain.”

Coastal geomorphologist, The University of Wollongong

It’s just plain wrong to assume that all atolls are washing away. It’s also wrong to sugar-coat the sobering facts that rising sea levels will ultimately seal the fate of low-lying islands and their limited soils and groundwater. The confusion isn’t surprising. It’s just more complicated than many expect.

“suggest that residents are fleeing atolls swiftly sinking into the sea. Yet new research shows that this is not the entire—or even an accurate—picture.”

Founder & Executive Director, Science Feedback

Scientists’ comments on this article clearly show that it is also not an “entire” or “accurate” picture. So Mr. Lomborg is using the very flawed reasoning he is condemning others of.

“Representatives from the Marshall Islands have been vocal about the need for strong global action on climate. President Hilda Heine has told reporters that longtime residents are leaving the Marshall Islands because climate change is threatening the nation’s existence.”

Professor, University of California, Berkeley

Mr. Lomborg cherry-picks studies relative to the global average. (Indeed, some areas of the Canadian Maritimes and Greenland are expected to see sea-level fall, but overall the rise is significant and a huge danger to the poor).

The idea that aiding the poor was an alternate to addressing climate change was wrong 15 years ago when I last debated Mr. Lomborg and is wrong today. False dichotomies are a sad refuge from the facts of both poverty and climate change.

Founder & Executive Director, Science Feedback

This is an interesting rhetorical trick by Bjorn Lomborg. So far he has only supported the point that ‘as of today, the area of many Pacific islands have not decreased’. But this doesn’t mean that ‘the islands existence is not threatened’, notably in the future as sea level rise becomes more severe. So here, he is swapping a weak claim that he has supported for a much stronger one that he has not, a version of the red herring fallacy.

“Those who seek to help should keep the bigger picture in mind.”

Professor, Victoria University of Wellington

Exactly Mr Lomborg. That’s why focusing on a small component of the story, in an area where many competing forces mask the underlying signal, is such a narrow approach. If one looks at the big picture of climate change, the loss of ice and snow, the increasing high temperature extremes, the already-apparent effects of sea level rise around the globe, the urgency of the problem becomes crystal-clear.

“Policy makers who want to help the residents of the Marshall Islands today should look at improving the islands’ resilience”

Research Associate, Harvard University

This is a classic technique in Lomborg’s articles: he focuses on one small aspect of climate change – here the Marshall Islands, other times maybe polar bears or heat-related human deaths – that i) he passes off as the main concern about global warming, and ii) that he can provide some seemingly contradictory information about… All the other consequences of global warming are conveniently set aside… Red herring.

“This will achieve almost nothing. My peer-reviewed research, published last November in the journal Global Policy, shows that even if every nation were to fulfill all their carbon-cutting promises by 2030 and stick to them all the way through the century—at a cost of more than $100 trillion in lost GDP—global temperature rise would be reduced by a tiny 0.3°F (0.17°C).”

Professor, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Dr. Lomborg sets out to show that the INDCs [emission reduction pledges] are useless. To do so he grossly misrepresents the pledges. He constructs an incomplete accounting that omits the pledges of many nations, ignores China’s pledge to cap its emissions by 2030, and assumes that the [European Union countries] will abandon their commitment to emissions reductions as soon as their pledges are fulfilled. (find more details in this rebuttal of Lomborg’s paper)

Professor, Victoria University of Wellington

The last IPCC report makes it very clear that following a path of strong emissions reductions can indeed cap warming at 2C or less, while business as usual would see 4-5C of warming this century. It is also now clear that meeting the Paris targets will likely save the West Antarctic ice sheet from melting, while other scenarios would see many metres of sea level rise, effectively destroying many of the major cities of the world. The costs of such inaction are almost incalculable.

“At a cost of between $1 trillion and $2 trillion annually, the Paris climate agreement, recently ratified by China, is likely to be history’s most expensive treaty. It will slow the world’s economic growth to force a shift to inefficient green energy sources.”

Research Associate, Harvard University

Not sure how these costs are derived—references would be good. […] These treaty costs may appear unprecedented, but so are the risks posed by climate change. Climate change “costs” are hard to quantify precisely – for instance, how to give a monetary value to the loss of certain ecosystems?—but likely to be quite significant. This recent study in Nature, for instance, indicates that: “If future adaptation mimics past adaptation, unmitigated warming is expected to reshape the global economy by reducing average global incomes roughly 23% by 2100 and widening global income inequality, relative to scenarios without climate change”.

- Burke et al (2015) Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature

Professor of Economics and Environmental Studies, Wesleyan University

There are hundreds of corporations who have signed on to reducing emissions in their own best interest (e.g. Walmart, DuPont, Chevron, Johnson and Johnson, Mercedes Benz, Dow… consult the White House website for an expanded list), reducing emissions and helping their customers do the same, for the benefit of their bottom line and their employees and their shareholders.

These companies know that they will make money working to reduce their carbon emissions (being first to get there). Their gains are not recognized by Bjorn’s cost estimates. This is not to say that it is free. It is to say that Bjorn’s Holy Grail of cost-benefit analysis should include the enormous deductions to costs from the market.