- Climate

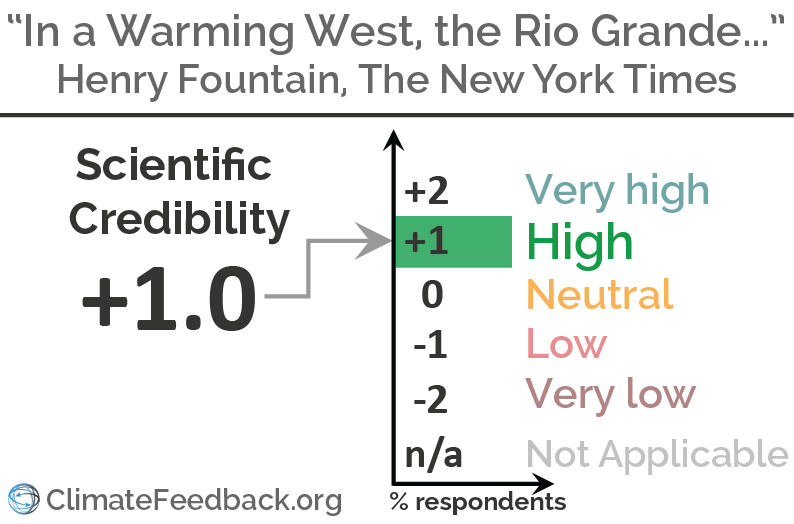

New York Times story accurately describes Rio Grande’s climate context

Reviewed content

Headline: "In a Warming West, the Rio Grande Is Drying Up"

Published in The New York Times, by Henry Fountain, on 2018-05-24.

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

This article in The New York Times discusses water supply issues along the Rio Grande in New Mexico, and the projected impacts of climate change.

Scientists who reviewed the article generally found it to be an accurate description of research on this topic. However, they note that it’s important to remember that precipitation in this region can naturally vary on timescales longer than just one year to the next. Even changes from one decade to the next should be considered carefully in the context of variability—and water supply risks depend on both human-caused trends and that natural variability.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Research Scientist, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Lab

I couldn’t find any serious flaws in the scientific information provided in this article, at least from an atmospheric / climate perspective. The issue of water resource management in the western US and how it fits within a changing climate is extremely complex and spans many disciplines from climatology to hydrology to city planning to population dynamics, and so on. This article does a nice job presenting the very basics of the climate science involved and tying the greater changes to the personal stories of people in the region. My only complaints are that the article uses a 14 year trend to discuss broader climate concerns without addressing low-frequency climate variability, and it misses out on an opportunity to discuss how regional climate feedback mechanisms play a role.

Project Scientist, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

I did not find any inaccuracies and most important aspects were included.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

Annotations

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

The monsoon rains he is counting on are notoriously unpredictable, however.

Yes, the main rain season is in the summer (July – August) but the main source for the rivers’ flow is the melting of the snowpack, which has been decreasing over time.

The Rio Grande is a classic “feast or famine” river, with a dry year or two typically followed by a couple of wet years that allow for recovery.

Weird wording. It’s just an arid river with high inter-annual variability in precipitation and flows.

If warming temperatures brought on by greenhouse gas emissions make wet years less wet and dry years even drier, as scientists anticipate, year-to-year recovery will become more difficult.

This is true, but it is a BIG IF.

Climate warming is expected to create intensification of the hydrologic cycle here as well, meaning that heaviest annual rainfall events may become more intense. So, overall—less rain, but the large storms will be even larger and create flash floods.

The effect of long-term warming is to make it harder to count on snowmelt runoff in wet times

This is true even if there is no large-scale change in overall precipitation in the watershed. Warmer temperatures will both increase local evaporation rates and cause an earlier and reduced snowmelt season. Both of these mechanisms reduce the availability of snowmelt runoff through the summer.

A study last year of the Colorado River, which provides water to 40 million people and is far bigger than the Rio Grande, found that flows from 2000 to 2014 were nearly 20 percent below the 20th century average, with about a third of the reduction attributable to human-caused warming. The study suggested that if climate change continued unabated, human-induced warming could eventually reduce Colorado flows by at least an additional one-third this century.

While this statement is largely true, it is important to note that 14 years is a relatively short time period, climatologically speaking. Moreover, this paragraph largely glosses over the key finding of this study, which is that temperature increases ALONE (i.e., in absence of changes in precipitation) are likely to cause a runoff reduction of about 6-7% per degree Celsius of warming.

This means that there is increased certainty that the southwest US will experience more severe droughts in the future, even if there is heightened uncertainty in climate model regional precipitation projections.

Last year, though, was a wet one on the Rio Grande, with a strong snowpack in the winter of 2016-17 that allowed the conservancy district to store water in upstream reservoirs.

Wet years may actually be “wetter” than today due to the fact that a warmer atmosphere can hold more water. (For example, see Rasmussen et al, 2011*.) So, it’s likely that we’ll see occasional news reports concerning record snowfalls, or record annual snow accumulations in the Rocky Mountains, even as the region dries out and becomes increasingly prone to extended droughts.

- Rasmussen et al (2011) High-Resolution Coupled Climate Runoff Simulations of Seasonal Snowfall over Colorado: A Process Study of Current and Warmer Climate, Journal of Climate

Temperatures in the Southwest increased by nearly two degrees Fahrenheit (one degree Celsius) from 1901 to 2010, and some climate models forecast a total rise of six degrees or more by the end of this century.

I checked various sources and these numbers are about right, an increase of almost 2 °F, or +0.17/decade1.

Annual temperatures in New Mexico are projected to rise another 3.5 to 8.5°F by 21002.

- 1-Tebaldi et al (2012) The heat is on: U.S. temperature trends, Climate Central

- 2-NOAA Technical Report NESDIS 142-5 (2013) Regional Climate Trends and Scenarios for the U.S. National Climate Assessment. Part 5. Climate of the Southwest U.S.

True, but in the spirit of transparency, some models forecast only 1.5 -3 degrees of warming.

Dr. Gutzler said spring temperatures have an impact, too, with warmer air causing more snow to turn to vapor and essentially disappear. A longer and warmer growing season also has an effect, Dr. Overpeck said, as plants take up more water, further reducing stream flows.

And increased soil evaporation.