- Climate

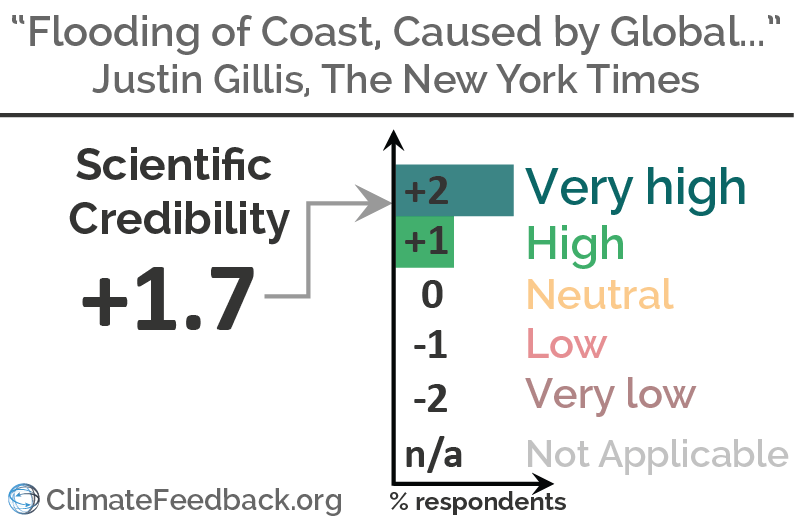

Analysis of "Flooding of Coast, Caused by Global Warming, Has Already Begun"

Reviewed content

Published in The New York Times, by Justin Gillis, on 2016-09-03.

Scientists’ Feedback

SUMMARY

Writing for the New York Times, Justin Gillis links the issue of global sea level rise due to climate change to examples of “sunny-day flooding” at high tide along the US East Coast.

The 12 scientists who reviewed the article found that it accurately described sea level data and research. Global sea level has risen about 20 centimeters (8 inches) over the past century, contributing to an observed increase in coastal flooding. However, multiple factors affect flooding in coastal communities and many locations along the US East Coast have experienced an even larger sea level change due to additional local factors.

The article also discusses research into future sea level rise based on records of past climate changes. While climate scientists generally think that sea level rise will not be greater than 1-2 meters (3.3-6.6 feet) this century, previous warm periods indicate that greater long-term sea level rise should follow in coming centuries—but precisely how much, and how quickly, is not well known. Around 125,000 years ago, for example, the Earth was probably about 1-2°C warmer than it is today, but global sea level may have been 6 meters (20 feet) higher.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context

GUEST COMMENTS

Professor of Coastal Engineering, University of Southampton

I find this a compelling piece of journalism translating our emerging scientific understanding into an accessible and credible form. It brings home to readers that sea-level rise impacts are being experienced today on the US Atlantic coast. The theory of sea-level rise and flood problems is pretty well understood — this makes the point that this theory is also happening now and can only be expected to get worse — sea levels have been rising on the US east coast for the last 150 years or more and even if current trends simply continue, impacts will continue to grow. As the article states, we actually expect a significant acceleration of sea-level rise in the coming decades meaning the impacts will grow more rapidly. The discussion of the public policy aspects of the issue is also important and shows that we need to start adapting to these changes now — they are only going to get worse.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall opinion of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Visiting Associate Professor, University of Wisconsin

This article is well-researched and demonstrates an understanding of the nuances related to the rates of sea-level rise, and how it varies in time and space. This article does a good job at conveying the state of the science and including supporting anecdotal information regarding the inundation of the coastal U.S. due to sea-level rise.

Research Associate, Harvard University

The parts of this article that report on climate science are accurate. In my view, the only thing is that issue of short-term (by 2100) vs long-term (next few centuries) sea level rise projections could perhaps have been explained a bit more clearly: even though total sea level rise by the end of the century is quite uncertain, a sustained 2°C warming almost certainly guarantees a 6 meters sea level rise over the next several centuries.

As far as I can judge, the article is scientifically sound and refers to up-to-date literature, interviewing knowledgeable scientists in the field. I would have liked to see a bit more nuance around the ‘melt’ of land ice though.

Assistant Professor, University of Virginia

This article supports local perspectives on sea-level rise in the United States with accurate, yet qualitative, scientific observations.

Chief Scientist for Climate Change Programs, Climate Institute

While there is no real discussion in this article about other factors affecting the coastline (e.g., land subsidence and emergence, local projects that affect movement of sand, the digging of trenches through coastal wetlands, etc.), the contribution resulting from global climate change affecting sea level rise is increasingly dominating the contributions of other factors in most locations.

That the present rise of a bit less than a foot since the 19th century is already having so much influence should help to justify the significance and concern in the scientific and defense communities and increasingly in some communities and states regarding the projected additional rise in sea level of two feet and possibly double that over the 21st century. The real uncertainty is becoming not how much the rise will be in the year 2100, but that the world is becoming committed to an ongoing rate of rise of a few to several feet per century, and that what is uncertain is exactly when that much rise will occur rather than if it will occur.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

Key Take-aways

The statements quoted below are from Justin Gillis; comments and replies are from the reviewers.

“Federal scientists have documented a sharp jump in this nuisance flooding — often called ‘sunny-day flooding’ — along both the East Coast and the Gulf Coast in recent years. The sea is now so near the brim in many places that they believe the problem is likely to worsen quickly.”

This refers to the historical analysis of “nuisance” tidal flooding frequencies (days per year) which we assessed in Sweet et al. (2014). In this report we looked at all tide gauges with hourly data since 1980 and with a threshold for “minor” impacts.

When minor flooding (nuisance) is expected, the Weather Forecasting Offices (WFO) typically issues a “coastal flood advisory”; they issue a coastal flood warning when levels are expected to reach moderate or major levels. The minor thresholds I started calling “nuisance levels” and the phrase caught on. Generally nuisance levels vary from 1-2 feet around the U.S.

The National Weather Service has a website (AHPS) that includes some of the tide gauge thresholds along with river gauges.

- Sweet et al (2014) Sea Level Rise and Nuisance Flood Frequency Changes around the United States, NOAA Technical Report

Project Scientist, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

This is accurate. Global sea levels have risen by about 20 cm due to human induced global warming in the last 100 years. Both US coasts have experienced this. It is true that subsidence on the east coast has exacerbated this and the last 20 years of natural variations on the west coast may have given folks a false sense of security because it has opposed or hidden the global rise experienced almost everywhere else.

“Along the East Coast, scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration say that many communities have already, or will soon, pass a threshold where sunny-day flooding starts to happen much more often.“

This relates to the Sweet and Park (2014) paper that uses a 30 days/year threshold as a definition of a tipping point. Though the 30 days/year threshold is somewhat arbitrary, it is sufficiently high that once a region experiences this many floodings, the conversation of what to do to address sea level rise tidal flooding has likely forefront.

The “soon” part refers to the fact that number of flooding days per year has (East and Gulf Coast locations) and will continue to accelerate with steady (linear) rises in sea level.

- Sweet and Park (2014) Acceleration and tipping points of coastal inundation from sea level rise

“These tidal floods are often just a foot or two deep, but they can stop traffic, swamp basements, damage cars, kill lawns and forests, and poison wells with salt.”

Visiting Associate Professor, University of Wisconsin

The depth of flooding is accurate as stated, as shown in Fig. 2 of Sweet and Park (2014)

“Federal scientists have documented a sharp jump in this nuisance flooding — often called ‘sunny-day flooding’ — along both the East Coast and the Gulf Coast in recent years.”

Professor, Earth Observatory of Singapore

This is a tricky one. Nuisance flooding on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts is the result of relative sea-level rise. Relative sea-level rise has a variety of components that give the rise a spatial signature. For example along the mid US Atlantic coast one-third of the rise is due to glacial isostatic adjustment with the remainder dominated by climatically driven sea-level rise. But in the Mississippi Delta the dominant driving force is subsidence. However, in the coming century these components will decrease in importance relative to climatically driven sea-level rise.

“Because the land is sinking as the ocean rises, Norfolk and the metropolitan region surrounding it, known as Hampton Roads, are among the worst-hit parts of the United States.”

Visiting Associate Professor, University of Wisconsin

This statement about the land sinking in the region of Norfolk, leading to higher rates of sea level rise is correct, and is supported by plenty of research, including: Kopp et al. (2014 Probabilistic 21st and 22nd century sea-level projections at a global network of tide-gauge sites, Earth’s Future)

“On the Pacific Coast, a climate pattern that had pushed billions of gallons of water toward Asia is now ending, so that in coming decades the sea is likely to rise quickly off states like Oregon and California.”

Senior Researcher, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement

This statement is likely to be accurate. Several papers already demonstrated the influence of decadal ENSO (El Niño) variations (or the Pacific Decadal Oscillation; PDO) onto the large-scale decadal sea-level variations in the Pacific Ocean (e.g. Zhang and Church 2012). Bromirski et al. (2011) specifically addressed the influence of decadal PDO/ENSO onto the west coast of America and demonstrated an influence of the PDO there, with a suppression of sea-level rise from the 80’s until 2005. As the decadal ENSO/PDO phase is reversing, there is over the past five years an accelerated sea-level rise over the west coast of America (Hamlington et al. 2016) that should continue in the next decade.

- Zhang and Church (2012) Sea level trends, interannual and decadal variability in the Pacific Ocean. Geophys Res Lett

- Bromirski et al. (2011) Multidecadal regional sea level shifts in the Pacific over 1958-2008. J Geophys Res.

- Hamlington et al. (2016) An ongoing shift in Pacific Ocean sea level. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans.

“In 2013, scientists reached a consensus that three feet was the highest plausible rise by the year 2100. But now some of them are starting to say that six or seven feet may be possible.”

Professor, Earth Observatory of Singapore

Yes, I couldn’t agree more. I actually wrote a paper regarding a survey of sea-level scientists. The concluding statement was that most experts estimate a larger sea-level rise by AD 2100 than the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report AR5 projects:

Horton, Rahmstorf, Engelhart, and Kemp (2014) Expert assessment of sea-level rise by AD 2100 and AD 2300. Quaternary Science Reviews

Professor, PennState University

In the 2013 IPCC report, there is a reference period (1986-2005), there is an assumption of a reference pathway of future emissions, and there is a confidence assigned to the estimate. That being said, I think the statement is pretty good. The second sentence is I believe accurate; the work by DeConto and Pollard, building on Pollard et al. (note that I’m involved in this study), for example, points to the possibility of rapid warming triggering rapid sea-level rise.

Senior Scientist, Carnegie Institution for Science

This is a correct statement, but a key word is ‘some of them’.

There have been some people, notably Jim Hansen, who, as I understand it, have been proposing high rates of sea-level rise without providing a mechanism for these sea-level rise rates that seemed plausible to most glaciologists. It is my understanding that the mechanisms proposed by DeConto and Pollard (i.e., mechanical instability of ice cliffs) does appear to be plausible and has some support in observations of ice shelf break-up that has already occurred in Antarctica. In other words, if this sentence were written a year ago, “some of them” would have referred to a few scientists who hold what might be considered ‘outlier’ views. Following the work of DeConto, Pollard, and others, my sense is that the risk of very high rates of sea-level rise seems substantially higher, even to what might be considered ‘mainstream’ scientists.

“But the air is already so full of greenhouse gases that most land ice on the planet has started to melt.”

Professor, PennState University

Not sure how I would parse “most of the land ice has started to melt”. It is true that there is net mass loss from most mountain glaciers, the Greenland Ice Sheet, and the West Antarctic ice sheet, which numerically makes most of the land ice. But, much of the ice remains too cold to melt, the big central region of East Antarctica is not melting, and much of the sea-level rise from the Antarctic is from faster flow into the ocean (after which the ice does melt…) rather than from melting in place.

I think this is not a very accurate statement and should be nuanced. Rather than ‘melt’, one should talk about ‘mass loss’ (or ‘mass gain’), as melt is not the only process adding to sea-level change. Especially on Antarctica, ice discharge [ice sliding into the ocean] plays a much more important role than melt, as over large parts of the Antarctic Ice Sheet (i.e. inland East Antarctica) the temperatures are so low that surface melt, even in summer, is not an issue at present (see eg these maps of Antarctica surface melt area).

If we step away from the ‘melt’ however, […] most glaciers on Earth are suffering from mass loss (IPCC AR5 Chapter 4: “Since AR4 (in 2007), almost all glaciers worldwide have continued to shrink as revealed by the time series of measured changes in glacier length, area, volume and mass”). […]

“In the worst-case scenario, this research suggests, the rate of sea-level rise could reach a foot per decade by the 22nd century, about 10 times faster than today.”

Senior Scientist, Carnegie Institution for Science

We published the results of a study in Science Advances last year (Winkelmann et al., 2015; Combustion of available fossil fuel resources sufficient to eliminate the Antarctic Ice Sheet) concluding that in a worst case scenario, sea level could be rising at an average rate of a foot per decade, averaged over the next 1000 years. Our model, however, did not include the mechanical instability of ice sheet cliffs considered by DeConto and Pollard (2016; Contribution of Antarctica to past and future sea-level rise), which could potentially result in sea-level rises of this magnitude. A key word here is ‘could’. More work needs to be done to assess the likelihood of this occurrence, but sea-level rise rates of a foot per decade by year 2100 appear to be a real risk posed by our greenhouse gas emissions.

“During ice ages, caused by wobbles in the Earth’s orbit, sea levels dropped more than 400 feet as ice piled up on land. But during periods slightly warmer than today, the sea may have risen 70 or more feet above the current level.

the last sea-level high point, … occurred between the last two ice ages, about 125,000 years ago. … scientists determined that the sea level rose by something like 20 to 30 feet in that era, compared with today. “

Research Associate, Harvard University

This part would perhaps be a little bit clearer for readers if it included estimates of global temperature change during these different times, to associate with these numbers on sea level change.

The last ice age, at its coldest, is estimated to have been on the order of 5 degrees Celsius cooler, in terms of global average, than today. As the article mentions, sea levels then were ~400 feet lower. The last interglacial preceding it, which Dr. Dutton’s research focuses on, was perhaps 1-2C warmer than today (today meaning the pre-industrial climate, before the warming of the recent decades). As the article indicates, sea-levels were perhaps ~6 meters higher at the time.

Citing these numbers would help put into perspective, for readers, the projected man-made warming of a few degrees Celsius globally, and explain why the long-term expectations of many scientists … are that sea levels will ultimately rise, over centuries, by “at least 15 or 20 feet” if the globe warms by several degrees in a sustained manner. The questions remains of course, how fast that will occur. Uncertainties on possible rates of sea level rise explain why sea level numbers by 2100 are so uncertain; but what’s virtually certain is that sea level will continue rising beyond that.

“Through decades of research, it has become clear that human civilization, roughly 6,000 years old, developed during an unusually stable period for global sea levels.”

Visiting Associate Professor, University of Wisconsin

The last 6,000 years have been unusually stable for the period of time that we are able to constrain rates of sea-level change particularly well (at sub-millennial timescales): see, for example, Lambeck et al (2014) Sea level and global ice volumes from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene.